Or how to live off the map

By Guy Thompson

I knew the drill.

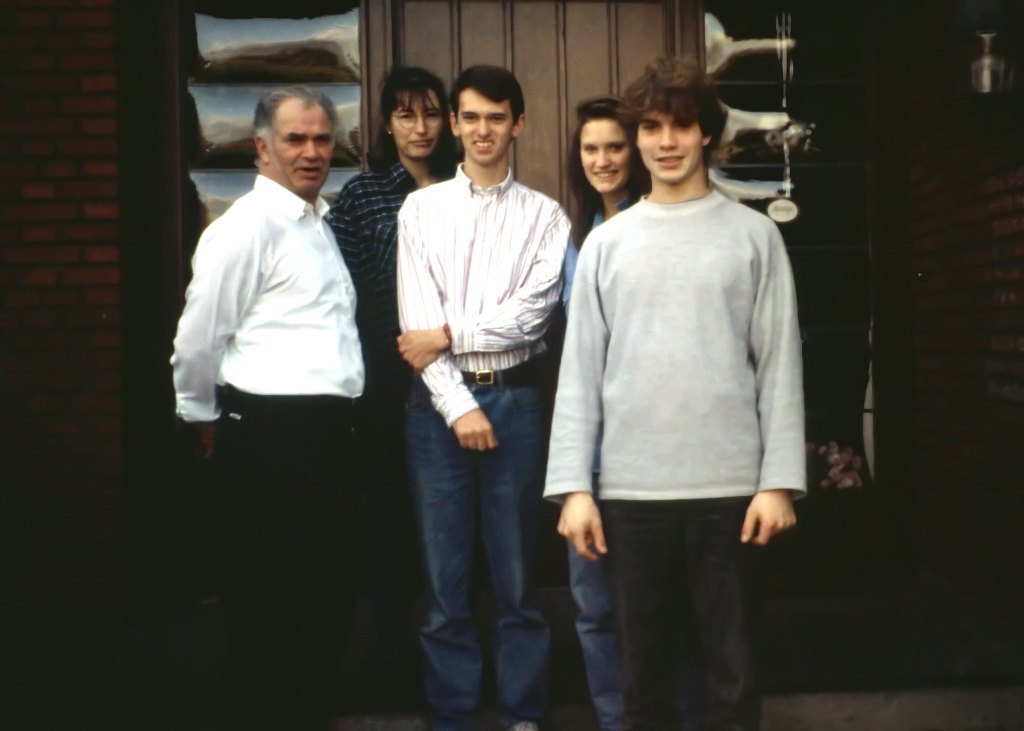

It was the last day with Family # 6, the Mackeprangs. That meant last-minute packing suitcases that still, somehow, weighed too much. Taking a last photo of two (though I always managed to realize later that there was something I really needed to take a photo of that I hadn’t done – such as the Porsche in Berlin.) Driving to the train station. Waiting on the station platform. Saying reluctant goodbyes. Waiting until the absolute last moment to get on the train.

Then, finally, leaving.

It was a drill that wasn’t any fun, but it had to be done a total of seven times. And this time, the next-to-last, would send me off to my final family, familie Höving.

The internal drill was also the same. It was still exciting, nerve-wracking, fun, and anxiety-inducing, all at once, to meet the new family. Regardless of where in the country I stayed, or what type of farm I ended up on, this part was always the same. And not knowing anything beyond the last name and address of the family really didn’t help at all with the anxiety.

The Landjügen representative here in the bundeslande (state) of Nordrhein-Wesfalen took us in their car to drop us off at each of our families. The car turned off a main road and then down what I initially thought was another side road, but turned out to be the long driveway back to my last host family’s farm. We got out of the car and Chris sniffed at the air. He guessed it was a horse farm, even though there were no animals in sight. I shrugged and thought that would be a new one. I had been on dairy farms, vineyards, and garden centers, but this would be my first with horses.

After we met the family, Chris and Melissa were whisked off to their families. Naturally, the first thing the Hövings did was to give me a full tour of the farm. There were no horses. There were, however, a lot of pigs and a barn full of steers. I’m guessing that Chris must have skipped MIT’s class on telling animal species based on the smell of manure.

It didn’t take long before I was into the rhythm of working with the Hövings – host dad Manfred, host mom Annette, host brother Dirk, and host sister Manuela (what?! No Carsten?!) – on the farm that sat back off the road that led to Warendorf-Freckenhorst. The city of Münster was about a half hour away to the west, but otherwise, the surrounding, mostly flat, landscape was dotted with small towns, each with a church spire sticking up from the center. I could usually see four to six towns any time we drove away from the farm. Which wasn’t too often.

Like most of the farms before this one, it was mostly work, most of the time. And like the farms that came before, I was sometimes delegated certain tasks that I would do for the duration of my stay. True, the tasks were definitely on the simple side. Help move cows toward the milking barn. Pull weeds. Paint fences. Shovel… mist. For the Hövings, I ended up with two standing responsibilities.

The first sounded simple enough when Dirk told me that I would feed the steers in the barn twice a day, morning and evening. (Fortunately, it wasn’t 5:30 in the morning.) Easy. It would involve bringing in silage from outside with a tractor. Easy. I can drive a tractor. Even in German.

Then I saw the maneuvering required to bring in the silage. Dirk demonstrated it once, and I realized that certain disaster lurked just over the horizon. In a nutshell, drive the tractor through the side door of the main barn. Then, make a sharp, 90-degree turn to the left, going up a small ramp to a level where the steers were kept. (The raised floor, as it turned out, allowed the… mist, to fall into a holding pen below.) This all sounds easy. But the part that spelled doom was the bit where, as one makes the sharp left-hand turn, while going up the small ramp, the bucket holding the silage had to swing through a gap between the railing and ceiling beam that looked, to me, no more than a millimeter bigger than the bucket.

I told Dirk, in a combination of German and English, that if he valued his barn, he would not let me drive the tractor through there. I can drive the tractor, sure, around wide open fields (and even manage not to hit hidden stumps.) I gave various examples of how the barn would surely collapse, each more graphic than the last, if I was allowed to try this maneuver. Dirk, the smart farmer he was, clearly valued his nice barn and everything in it, and drove in the silage into the barn, expertly swinging that bucket through effortlessly, each day, for me to pitch into the trough for the steers to eat. And because of this, the barn remains standing to this day (according to Google Earth.)

Along with the silage, got to eat the leftovers from the farm’s still. And, as it turned out, this was the second regular task I got to do each day. In all of my years, I never once would have guessed I would do – distill alcohol. Wheat schnapps, in this case. It wasn’t unusual to find a still in barns around the country. Back in the black Forest, a lot of the barns I had visited with host dad Otto had a still tucked into a small room somewhere in the barn. The stills were regulated and sealed; the alcohol was sold to whichever government agency handled that sort of thing.

Each afternoon, I would watch the still, noting temperatures and pressures and, when the temperatures and pressure gauges read certain numbers, I would twist little knobs on the still to make the numbers on the gauges change back to what they were supposed to be. Looking back, I now realize that “Distilling sheat schnapps” is something I should have put on my resume after I got back to the states and started job hunting. Sure, being an international exchange student looked great, but how many applicants could say they can distill schnapps? I’m sure I would have stood out in the job interviews.

Like many of the other families before them, the Hövings took the opportunity with an extra pair of hands on the farm to tackle a special project or two. Things that they had probably been meaning to get to, but couldn’t spare the time because there was just so much other stuff to do. In this case, the Hövings didn’t just call upon myself, but brought in two of Dirk’s friends (of whom, at least one was also called Dirk) to put a new roof on the barn. And German roofs are no lightweights. Up north, I saw more than a few places that still had the traditional thatched roof, both houses and barns. Here, like most everywhere else in the country, the roofs were tiles, very heavy terra cotta tiles that weighed around five pounds each. To take off the old tiles, once clambers up onto the roof and begins pulling the tiles up. Nothing holds them on, save for their own weight. Then – heave! With a bit of practice, one can lob tile after tile through the air to land in the wagon below.

Next up, putting the new tiles on the barn. And while this doesn’t seem particularly dangerous, as it turns out, it can be. Host dad Manfred would bring a pallet of the new tiles around and place it across two thick boards laid across the top of the farm wagon. The boards would bend, but hold the weight, unless, that is, an American exchange student happens to be standing on the boards at the same time. Then – CRACK! Tiles and American student alike go crashing into the bottom of the wagon. Fortunately, the American student landed on top of the tiles and not the other way around. The look of sheer terror on Manfred’s face was clear. I could see him wondering how the heck he was going to compose a letter to my family telling them how he had accidentally crushed the American student with roof tiles.

##

As noted at the start of the last chapter, it may seem that I did less with the last two families than anywhere else during my stay. And, in some ways, that was true. Did I want to go see the castle 30 minutes away? Well, was it like the other castles? Actually, yeah, it was. So let’s just stay home and hang out!

The towns of Warendorf-Frankenhorst were square little jewels set in the green German countryside. Freckenhorst had a town square that was the perfect representative of all German town squares that had a flea market on the weekends. Warendorf was like Freckenhorst to a large extent, and just as picturesque. We drove to Münster a few times, perhaps to visit the fußganger zone (pedestrian shopping area) or head over to their big annual festival. German festivals are something to behold, each a different version of a large county fair. Rides lit with neon and the barkers yelling at everyone play their game. You were sure to win!

Six months earlier, sitting in the Hotel am Zoo in Frankfurt, and searching for each of my host families’ towns on a tourist map, and not finding them because most of them weren’t places tourists apparently went to, I had been a little worried. Not a lot, mind you, but the initial feeling was wanting to stay near the “cool” places that had castles, majestic landscapes, and all of the sites the tour books mention. Like Berlin, a city that has entire guide books dedicated to just itself. All of the other towns I ended up living in rarely, if ever, get mentioned in those books, except perhaps being mentioned by the writer as a town for the tourist to pass through as the tourist heads to the real destination.

But those tourists miss all of these great towns like wWarendorf-Freckenhorst, or Weilburg, or Elsfleth. They would even miss the quiet suburbs of Berlin. Now, over 30 years later, when I’m fortunate enough to meet an exchange student living in our small, out of the way part of the world, I cringe a little to hear someone say, “Oh, I’m so sorry you ended up in the middle of nowhere.” Hey, I’ve been that exchange student living in the middle of nowhere, and those places remain some of my favorite places I’ve ever stayed. And while an exchange student to our area will likely get to go to Chicago, or Detroit, or even New York or Disney World, as host families will want to take them to those places, that’s not why they’re here. That wasn’t why I was there. It’s about living like a native of that country.

It’s about living in the places that you can’t find very easily on a map.